- Home

Page 5

Page 5

Murder at the Ritz

Murder at the Ritz Murder at Madame Tussauds

Murder at Madame Tussauds Murder at the Manchester Museum

Murder at the Manchester Museum Blood On the Wall

Blood On the Wall 4.3.2.1

4.3.2.1 Jungle Kill (Black Ops)

Jungle Kill (Black Ops) Murder at the Natural History Museum

Murder at the Natural History Museum Murder at the British Museum

Murder at the British Museum Assassins

Assassins Hunk and Thud

Hunk and Thud Roman Invasion

Roman Invasion Big Rock and the Masked Avenger

Big Rock and the Masked Avenger The Last Enemy

The Last Enemy Urban Assassin

Urban Assassin The Deadly Game

The Deadly Game Alan Turing

Alan Turing The Lethal Target

The Lethal Target The Giant Rumble

The Giant Rumble Codename Céline

Codename Céline Death in the Desert

Death in the Desert Escape from Pompeii

Escape from Pompeii The Invisible Assassin

The Invisible Assassin Shadows of the Dead

Shadows of the Dead Jack Versus Veto

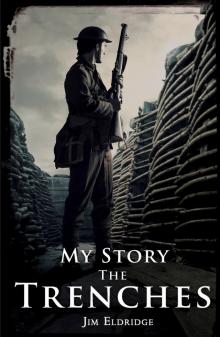

Jack Versus Veto The Trenches

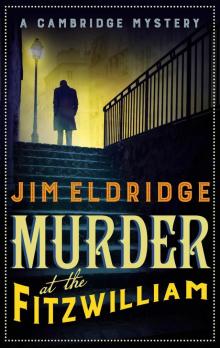

The Trenches Murder at the Fitzwilliam

Murder at the Fitzwilliam Coming Home

Coming Home